Research question: narrow your terms

Part of Big Questions Little Questions (BQLQ), critical thinking skills for sixth form students from the University of Oxford

![]()

We have talked about why your research question matters and the first steps that you need to take in identifying and formulating it. But most of us will find that our initial ideas are too big, too broad, or simply impossible to address adequately within the time or budgetary constraints we are given. This is normal. The more we learn about a topic or question, the more we see that there many smaller questions and subtopics, and we realise that we need to narrow down our terms.

Here we will look at how you can move from your broad areas of interest to more specific, concise, and appropriately-bound questions. This is not always easy, and often researchers will struggle with compressing their broad topics of interest and big questions into a smaller question that they might be able to complete in the time available. Usually it takes several revisions to go form an interesting topic to a concise, focused, and specific research question.

What makes a good research question?

Research questions help writers focus their research by providing a path through the research and writing process.

A good research question is a guide.

It is worth spending time at the beginning of a project on developing and refining your research question.

Clear: each term you use needs to be well defined so that it marks out exactly what you will and will not be concentrating on.

Focused: if it is too narrow it will be boring and easy to answer; too broad it will be unmanageable and probably impossible to finish

Complex: is the complexity of the subject within the scope of the project and within your ability? It needs to be hard enough to be interesting, but not too complex to make it impossible to finish in the time that you have. is it objective enough to warrant research, or is it going to be down to a matter of opinion? Or is it so objective that it is just factual and obvious? Are there different perspectives that deserve analysis?

Researchable: are there primary and/or secondary sources?

Deliverable: do you have the budget and the time to gather the data and information you will need and also the time to write it?

What do we mean by concise and specific?

Think about the example that we gave earlier, about studying the representation of biology in art. Art is a very broad term: whose art? what period? what type of art? Likewise, biology encompasses anything from bacteria to planet-wide ecosystems, so we’d need to narrow that down too. If this led us to decide to focus on the human body and how it has been artistically represented in the past, and from there to Leonardo da Vinci, suddenly our investigation could find greater focus. For example we could ask how da Vinci’s illustrations of anatomy influence the representation of the human body by subsequent artists, or how his approaches differed from modern medical texts, or how they influenced popular understanding of the human body. From here we would need to narrow it down a bit more to something that could be manageable within the time you have to complete the research. This might involve picking a particular artist or small group of artworks to compare against, or a single modern illustrated medical text, or a particular pop culture reference point.

You can probably start to see the importance of exactly how your question is worded. Once you have a draft research question, you must go through each word one by one and test whether it’s precise enough. Ask yourself: is this term too vague or ambiguous? Is it too broad? how can I narrow it down further?

Choosing your words carefully

Question words can be broadly separated along a range with the two extremes being descriptive at one end and critical at the other:

- Critical: requires you to reflect and offer observation, opinion and reflection, for example: account for, analyse, assess, criticise, determine, evaluate, justify, prove.

- Descriptive: requires an account and can be less challenging and less interesting e.g. describe, measure, record, summarise.

Avoid questions that can be answered simply with a yes/no response.

Why questions: often too many possible causes. Often TOO open. It may be better to use ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions

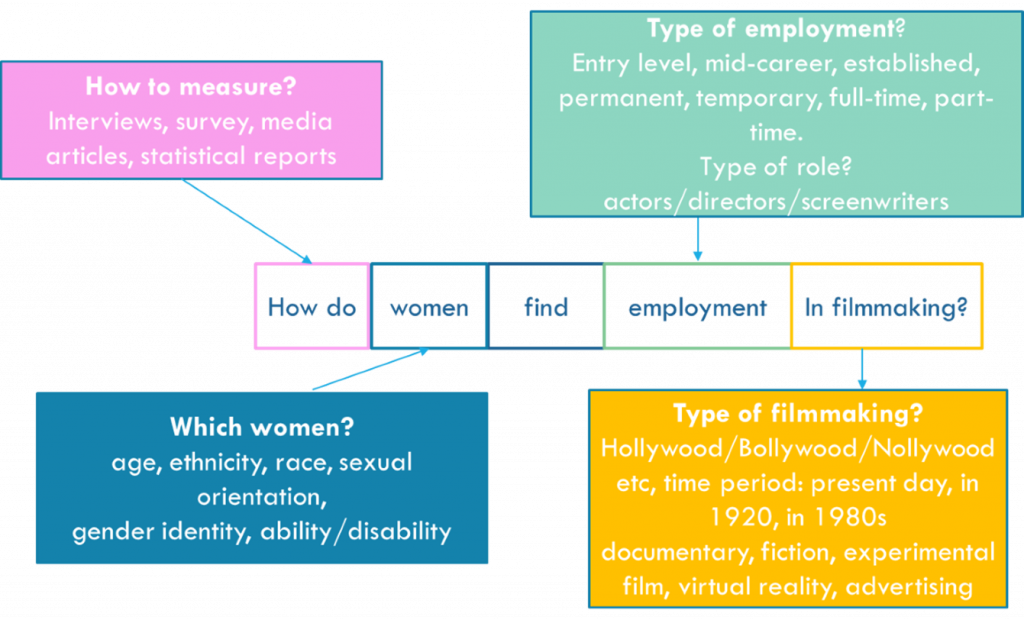

A good technique to help you make your question clear is to explode terms. This means looking at each part of the questions and clarifying and identifying what you mean.

Take a look at the following example. On the surface, it looks like a good research question, but have a think about possible issues or ambiguities that could lie in each term that makes up the question. This is called exploding the terms. Try to think of a more specific and precise research question that this student could ask instead.

In developing your question, as in your actual investigation itself, try to focus on the analytical aspects rather than the descriptive. This can be reflected in the types of question words that you choose. Descriptive responses tend towards being a bit a collection of facts with no real point. Analytical responses tend to be more critically engaged, showing that you have thoughtfully asked the right questions, at the right time, about the right thing. Crucially, critically-engaged, analytical investigations usually make a cohesive argument that have a point to them.

You should aim to hone your critical thinking skills throughout your investigation, analyse the topic fully, and come up with your own ideas and answers rather than repeat already established views. A good way is to focus on the hows and whys rather than the whos and whens.